Who Qualifies for the Cognify Clinical Trial?

Alberto Rivera • January 16, 2026

Inclusion Criteria

Who Can Join?

To be eligible, the person must:

- Be 56 years or older

- Have a diagnosis of dementia from a Neurologist (Alzheimer’s, vascular, Lewy body, frontotemporal, or mixed)

- Score between 5 and 24 on the MMSE (Mini-Mental State Exam)

- Have tried and failed at least one standard dementia drug (e.g., Aricept, Namenda)

- Be ineligible for other clinical trials

- Complete a saliva test showing compatibility with TB006

Recent Posts

By Alberto Rivera

•

January 16, 2026

When a promising new treatment is not yet fully FDA-approved, patients with serious conditions may be able to access it through something called an Expanded Access Program These programs are designed for people who: Have a life-altering or progressive illness (like Alzheimer’s) Are not eligible for a clinical trial Have no other effective treatment options Are under the care of a licensed physician who follows FDA and safety protocols Expanded Access allows patients to receive an investigational drug under close medical supervision while more data is being collected. It’s not a guaranteed treatment, but it can offer hope when standard care has failed . That’s exactly what the Cognify Program is doing. Expanded Access Programs are selfpay Providing access to the investigational drug TB006 for qualified individuals

By Alberto Rivera

•

January 16, 2026

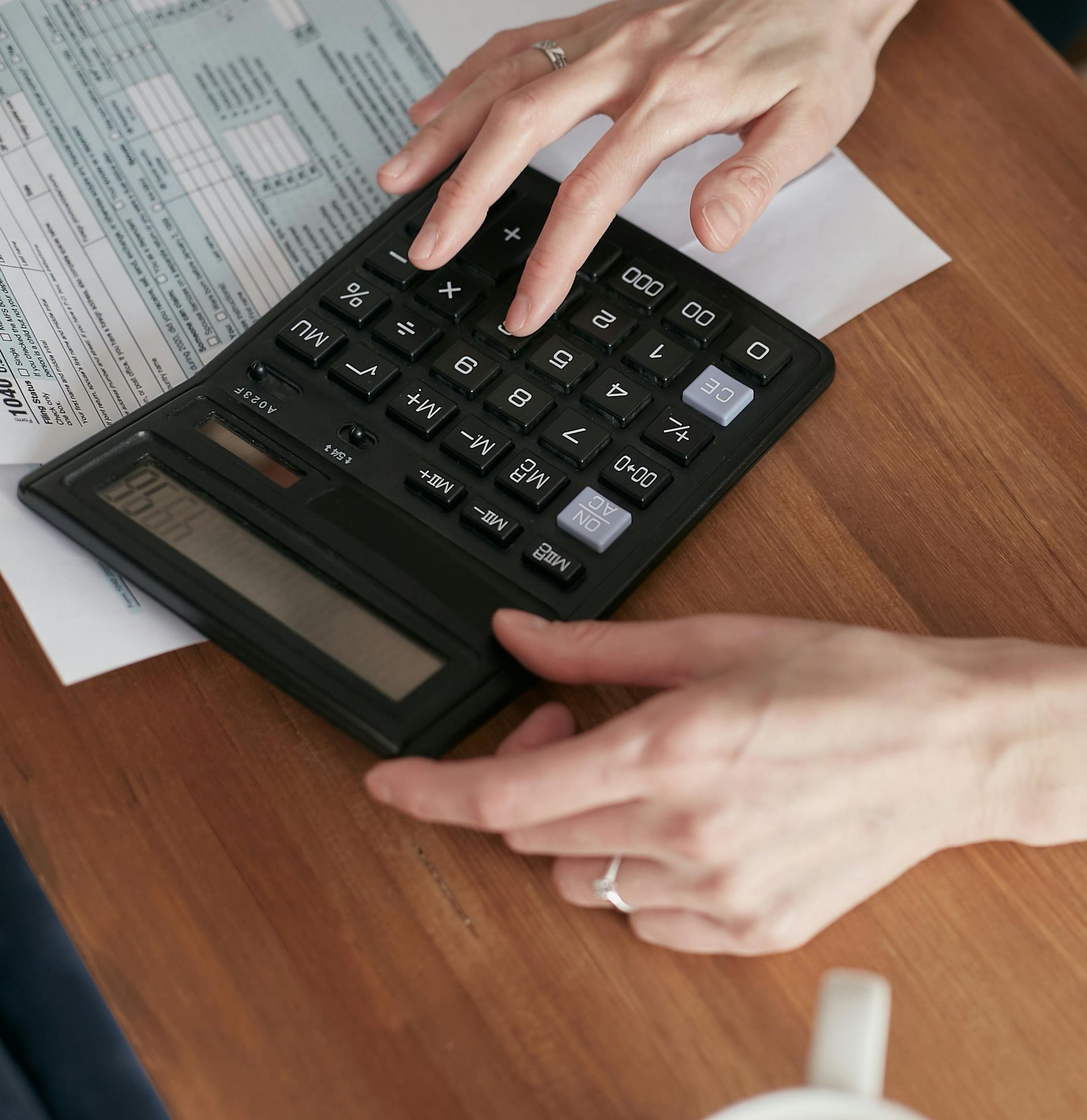

Average Disease Horizon People with Alzheimer's typically live 4–8 years after diagnosis (often cited conservatively as ~ 7 years ), though this varies widely by age at diagnosis, sex, comorbidities, and other factors. Some survive 20+ years, while others have shorter courses. Recent meta-analyses (including 2025 publications) confirm this range, with longer survival often seen in women, earlier diagnoses, and pure Alzheimer's (vs. mixed dementias). Annual Costs Per Patient Using figures that align closely with Alzheimer's Association reports and economic studies (2023–2025 data, adjusted for conservatism): Formal medical + long-term care (hospitals, facilities, home health, etc.): ≈ $30,000/year (National formal costs reach ~$384 billion in 2025 across all patients, with per-patient formal expenses often in the tens of thousands, rising sharply in severe stages.) Out-of-pocket expenses borne by families : ≈ $9,000/year (This covers gaps in insurance: medications, supplies, home modifications, transportation, and uncovered portions of care. Recent caregiver studies show averages of $7,000–$12,000+ annually, with families shouldering ~25% of total formal costs nationally via $97 billion in aggregate out-of-pocket spending in 2025.) Economic value of unpaid (informal) caregiving : ≈ $36,700/year (This reflects the replacement cost of family-provided care — time that could otherwise be spent on paid work or personal life.) Total societal economic burden per year : ≈ $75,700 (formal + out-of-pocket + unpaid care value). Over a 7-year horizon, this accumulates to roughly $530,000 per person — a figure that underscores why Alzheimer's is one of the costliest conditions. Unpaid Caregiving Intensity Families provide the majority of hands-on support. On average: ~31 hours/week (≈ 1,612 hours/year ), per Alzheimer's Association-aligned data (2023–2025 reports and recent studies show caregivers for dementia patients averaging ~31 hours/week, significantly higher than for non-dementia conditions). Over 7 years: ≈ 11,300 hours total — equivalent to more than 5 full-time work years diverted from employment, self-care, and other responsibilities. These hours often lead to major life disruptions: reduced work hours, leave of absence, early retirement, or job loss — compounding financial strain and emotional exhaustion. Key Implications and Nuances Variability : Costs escalate dramatically in moderate-to-severe stages (e.g., nursing home care can exceed $95,000–$108,000/year). Early diagnosis or slower progression can moderate the burden. Family burden : Families bear ~ 70% of lifetime costs through out-of-pocket payments and unpaid care value (national lifetime estimates exceed $400,000 per person). Broader context : National unpaid care exceeds 19 billion hours annually (valued at >$413 billion in 2024–2025), with dementia caregivers reporting twice the emotional, physical, and financial strain compared to others. These conservative numbers highlight the urgency: Alzheimer's isn't just a medical challenge — it's a profound, multi-generational economic and human crisis for families across the US. (Sources: Alzheimer's Association 2025 Facts & Figures; recent meta-analyses on survival; economic burden studies 2024–2025. Figures used conservatively for illustration.)

By Alberto Rivera

•

January 9, 2026

In clinical medicine, timing is rarely emphasized enough. Two people can share the same diagnosis and live in completely different biological realities. One may change slowly. Another may decline rapidly after a relatively minor stressor. The difference is often not age, effort, or intent, but where the disease sits on a biological timeline. In Alzheimer’s disease, this distinction matters deeply. There is a phase in which inflammation and immune signaling dominate. There is another in which structural damage overwhelms the brain’s ability to adapt. Strategies aimed at modulating signaling pathways are most relevant in the former, not the latter. This is why timing is not about urgency. It is about appropriateness. Waiting often feels cautious. It can feel respectful of uncertainty. But biologically, waiting is not neutral. Immune signaling, once established, tends to reinforce itself. As that reinforcement continues, flexibility narrows and options change. Understanding this does not obligate action. It simply reframes the cost of delay. Programs that explore biologic interruption strategies are built around this reality. They emphasize evaluation, selection, and realism, not promises. They are not for everyone, and they are not appropriate at every stage. But for those who may still fall within a window where biology can respond, awareness matters. Families often say they wish they had understood this distinction earlier, not because it would have guaranteed a different outcome, but because it would have changed how decisions were weighed. Because in medicine, the right question at the right time can matter as much as the answer.

By Alberto Rivera

•

January 9, 2026

One of the most difficult aspects of Alzheimer’s disease is not what happens, but why it continues. In healthy biology, inflammation follows a predictable pattern: activation, resolution,and repair. It turns on when needed, and just as importantly, it turns off. In Alzheimer’s, that off-switch often fails. Research over the past decade has highlighted the role of a regulatory molecule called Galectin-3, a protein involved in immune signaling and cellular communication. Galectin-3 does not cause Alzheimer’s in isolation. Rather, it appears to stabilize and reinforce inflammatory signaling, keeping immune cells in an activated state long after the original trigger has passed. This phenomenon is sometimes described as immune lock-in. When immune cells remain locked in an activated posture, they stop behaving like repair crews and begin behaving like chronic responders. Over time, this persistent signaling alters the brain’s environment, affecting neuronal resilience, clearance mechanisms, and functional stability. This helps explain why many Alzheimer’s therapies that focus only on symptoms or late-stage findings struggle to change outcomes. They are working downstream, while the signal that sustains progression remains active upstream. Understanding this biology does not create certainty, but it does create coherence. It explains why decline often continues despite compliance, support, and best intentions. Modern investigation is now asking a different question: not just what accumulates in Alzheimer’s, but what keeps the immune system engaged when it should stand down.

By Alberto Rivera

•

January 9, 2026

In medicine, the most meaningful advances rarely come from what is most visible. They come from what has been quietly ignored. For decades, Alzheimer’s disease has been discussed primarily in terms of memory loss, plaques, and symptoms that appear late in the process. Treatment strategies have largely focused on managing consequences, while the underlying biology that drives progression continued unchecked. What has become increasingly clear in advanced research is that Alzheimer’s behaves less like a disorder of memory and more like a condition of persistent cellular distress and unresolved immune signaling. This is where progress begins to look different. Rather than focusing only on what accumulates in the brain, modern investigation is asking deeper questions: Why do inflammatory signals remain active? Why do immune cells stay engaged long after their role should be complete? How does ongoing signaling quietly reshape brain function over time? These processes occur at a cellular level, far beneath what imaging or cognitive testing can detect. Yet they strongly influence whether decline accelerates, stabilizes, or becomes unpredictable. Programs that explore this biology are not built around urgency or promises. They are built around understanding, how immune modulation, cellular communication, and signaling balance may influence disease trajectory when approached thoughtfully and early enough. At first, this perspective may seem unconventional. But in clinical medicine, it is often the unconventional question that explains why conventional approaches fall short. Those who take the time to understand these deeper mechanisms often describe a shift, not in certainty, but in clarity. And clarity changes how decisions are made. The conversation around Alzheimer’s is evolving. Not quickly. Not dramatically. But meaningfully.